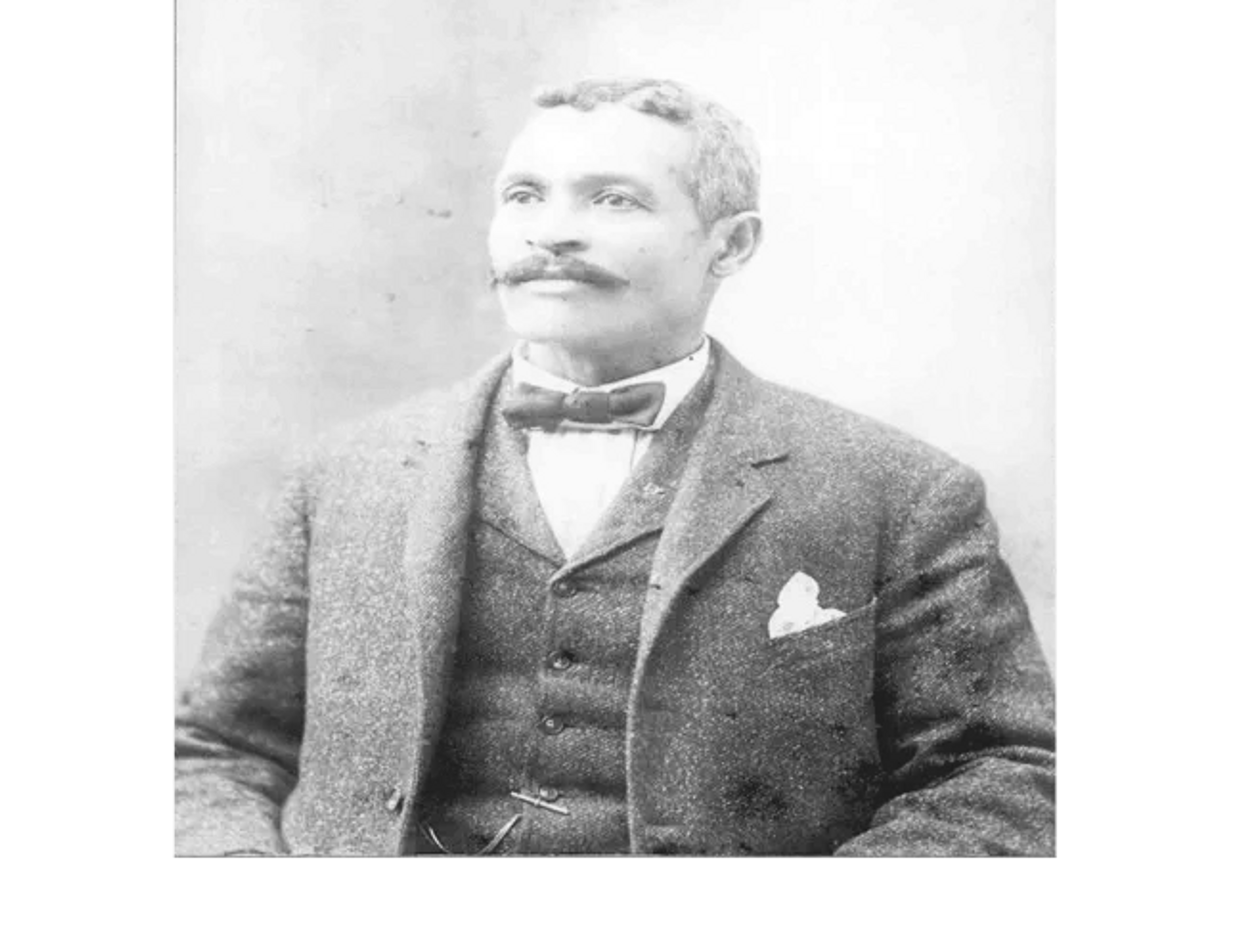

CAPTAIN JAMES CAMPBELL

HIS FAITH

Captain James Campbell was a man of faith. In his Bible, he kept an accurate record of his wife and children by their names, birth and death dates, as well as personal notes. The wealth of hymnals, Bible literature, and Christian materials in his home indicate that the LORD was an important part of his life and in the lives of his family. They regularly attended Mt. Pisgah AME Church located two doors down from his

home and actively participated in the operations of the church.

Mt. Pisgah ministered to the local community as its neighborhood church for families of color. It provided an ideal place of worship and services gave members the opportunity to praise and acknowledge the LORD for HIS goodness to them. Florance, one of Campbell’s daughters, even wrote in her hymnal how she had joined church at the age of fourteen. She and her sister, Emma, particularly worked in the church faithfully and held various offices throughout their adult lives, such as Church Clerk and President of the Trustee Board respectively.

Congregational hymns such as: “We’ll Understand It Better By and By”, “Nothing Between”, and “I’ll Overcome Someday” (later known as “We Shall Overcome”) were probably sung by James and his family. Interestingly enough, these songs were all written by an United Methodist Pastor, Charles Albert Tindley (1851-1933). Tindley was a “free” Black man and contemporary of Captain Campbell. He was also a singer, songwriter, and composer who was the first to copyright church songs. The forty-seven hymns that he wrote gave hope and encouragement to those who

sung them and inspired all to lean on GOD whenever going through trials.

Originally established in 1862, Captain Campbell’s home church, Mt. Pisgah, was incorporated in 1876, and built in 1877. It still stands today and holds services at 169 North Lincoln Avenue in Washington, N.J. Currently, certain local Campbell descendants are members and most relatives, who have moved away, traditionally come back for yearly Homecoming celebrations.

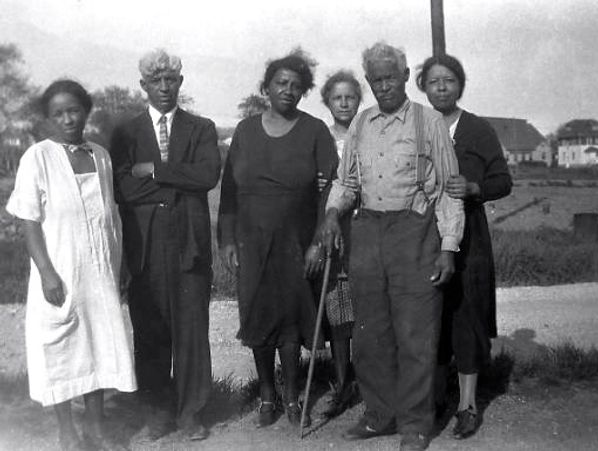

HIS FAMILY

James Campbell was born on January 16, 1856 and died on June 5,1932. He was a “free” born African American male who could both read and write. On October 9, 1878, at the age of twenty-two, James married Hannah Kathleen Anderson. They had eight children: Frank, James Albert, Emma Kathleen, Nicodeamias (Nicodemus), Lorita (Loretta), Florance, Reaves, and Elizabeth. Tragically, their son, Frank, was “lost” at the age of eight and the rest of the boys died young. His daughters, however, grew up and married. Emma and Loretta, two of the sisters, married two cousins, James Groves and George Groves. Florance married Charles Van Horn and Elizabeth

married George Johnson.

Campbell’s girls loved him very much. Their deep regard and attachment to their Father was evident in many ways: Emma, his eldest, led the mules along the canal towpath countless times for him as they travelled from Phillipsburg to Jersey City. She made sure to climb up on the mules, as instructed by her parents, to keep from getting bitten by snakes. Florance, at twelve, skipped school sometimes, wanting to be with her “Pop” on the canal. In spite of doing “boat” chores, such as washing dishes, making coffee, and cooking on the little stove inside the boat’s cabin, Florance was content. These things didn’t matter because she was with “Pop”.

Florance and “tomboy” Loretta also “drove” the mules, walking barefoot along the towpath and climbed up on them when tired. Loretta, affectionately called Captain Campbell, “Papa”. This was her special name for him. As a young woman, she even wrote letters addressed to him that way when employed away from home.

Then, Elizabeth, was his “Baby Lizzie” and to her he was “Dad”.

Campbell’s wife, Hannah, was the love of his life. She was born on March 7, 1858 in New York and died on November 23, 1900 due to surgical complications. Hannah was only forty two years of age at that time. She worked steadily along side of her husband on the boat and in emergencies had to steer the boat for him. Hannah made their house a home even when faced with the loss of her sons. Church attendance, canning, quilting, gardening, sewing, cooking, music, and more were all a part of her life.

HIS CHILDREN (in order)

- Frank Campbell (1895 - Lost! 1883) 8 years old

- James Albert Campbell (1879-1884) 4 years, 2 months old

- Emma Campbell Groves (1881-1986) 105 years old

- Nicodeamias Campbell (1883-1893) 9 years old

- Sorita/Lorita/Loretta Campbell Groves (1887-1948) 61 years old

- Florence Campbell Van Horn (1889-1978) 89 years old

- Reaves Campbell (1892-1893) 1 year, 7 days old

- Elizabeth Campbell Johnson (1896-1974) 78 years old

HIS WORK & HOME

Captain Campbell, or “Jim Camel” (Cammel) as he was known by other canal captains, skillfully navigated canal boats through the Morris Canal for over forty years. He became one of only a small percentage of Black Boat Captains on the Morris Canal.

At the age of fifteen, he followed in the footsteps of other family members, “canalers”, who had been Boatmen before him.

Captain Campbell, along with other African American workers, were “active” participants in the daily operations of the Morris Canal which helped to positively affect the economic growth and development within New Jersey.

A boy or young man, called a “boat hand”, drove (led) the mules and was responsible for their care throughout the trip. When the journey ended, he was the one who made sure that the animals were boarded in the company’s stables. At seventeen, James’ younger brother, Nicodemus, lived with him and helped drive the mules. They worked together getting the jobs done. At other times, Campbell’s girls did part of this work. One mule named “Katie” was easy-going and would let the girls climb on her when they were tired but “Jenny” was a kicker and would’t allow it.

Getting an early start on weekdays was essential because this job was hard work and done in rain or shine. One trip took about five days and having your boat equipped with its necessary supplies was important. Time equalled money and arriving at the boat yards on time was to the Captain’s advantage. His diligence allowed him to make enough money to keep his family adequately provided for throughout the winter months. Then, in that “off” season, from mid-December to the end of February, he sometimes opted to work at the Terra Cotta Works in

Port Murray, NJ “brickyard”.

Boat provisions were stored in special areas. Salt mackerel (called “kits”) were bought by the pail and kept close to the boat’s hinges, in the cabin, wrapped up. Bacon was stored there as well. Ham and eggs, however, were kept with the oats in one of two feed chests and fresh milk was purchased only occasionally in Bloomfield or Paterson. Typically, a weekday meal consisted of ham, bacon, and eggs. Sunday meals were a change from the norm though and stews and puddings were prepared at that time.

Boats did not operate on Sundays. When docked overnight by Bloomfield, a local Minister came and invited all of the children from the various canal boats to his church. The Campbell girls got to attend Sunday School and church there, barefoot and all! They learned Bible lessons about keeping God’s Ten Commandments;

lessons they never forgot.

Another time, during a rain storm, Florance and Loretta were running around on the hinge section towards the back of the boat. The deck became very slippery and Hannah repeatedly warned the girls not to run. They didn’t listen and Loretta ended up in the Canal! Captain Campbell had to get the “pike pole” (a long pole with a sharp hook on one end) and carefully “hook” it onto her clothing. He was able to pull her over to safety onto the towpath. This situation could have been tragic though because she could've drowned or been stabbed badly with the pike pole.

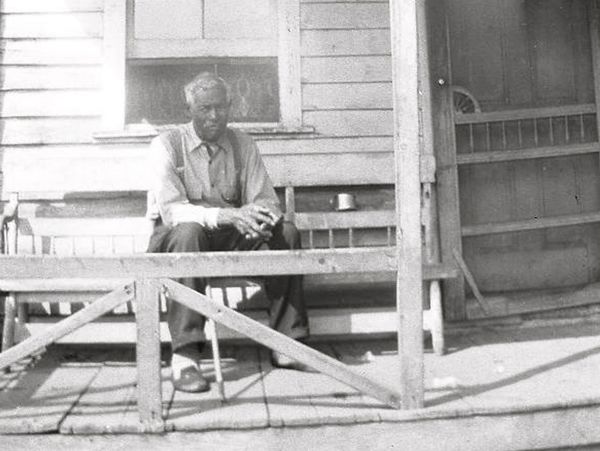

After his “boating” days were over, Captain Campbell worked for the Canal Company in their maintenance department, was a Teamster, and employed by the local Water Company as well. He never really retired.

His house (c.1860) represents him and his occupation as the most authentic legacy left standing across from the Canal. Its purchase price in 1889 was $167.98, an equivalent price of $5,511.13 today where $1.00 then equals $32.81 now! This dwelling, located at 163 North Lincoln Avenue, served as the family’s residence throughout Campbell’s Boatman career and was once part of a thriving,

well-established African American district. These working class families were an asset to their community.

Beside the home itself, the Campbell property featured a large barn with a haymow where his mules were kept. These animals could be borrowed or left to rest there for short periods of time. When by some misfortune a Canal family’s mule was injured or died, Captain Campbell would lend his mules to them regardless of color.

His kindness was appreciated and noted in the interviews of Canal families in the book, Tales the Boatmen Told by James Lee.

Stay On the Right Path.

Campbell Cultural Heritage House, Inc.

P.O. Box #397, Washington, NJ 07882

Website designed by Angelique Benton

Copyright © 2024-2025 Campbell Cultural Heritage House, Inc. - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.